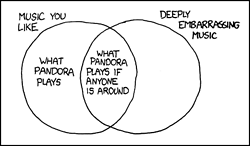

Pandora is an online music streaming application that plays music based off of what you listen to and enjoy. If someone overheard your Pandora account playing a bad song, they might assume you like bad music. Following Murphy’s Law, one could presume that Pandora would only play these bad or embarrassing songs while another person was listening.

The author created a diagram from an almost humorous observation he made while on his computer.

A female is seen playing SkiFree, a classic 1991 computer game that involves skiing an endless slope while escaping a violent monster.

While playing the game, the female contemplates the metaphorical connection between the inevitable in-game death at the monsters claws with death in real life.

But, no sooner than her thought is complete, a male character informs her of a secret that will allow her to escape the clutches of the monster and, thereby, in-game death. This leaves her in a confused state as she contemplates the possible avoidance of all forms of death.

A man in a black hat explains an elaborate prank involving crime and breakthrough mechanical inventions that he has been playing on the president of the Skeptic’s Society - a group dedicated to fighting superstitious and irrational beliefs. In this prank he breaks into the man’s house and rearranges things using “silent tools,” as well as making ghostly noises and even knocks him out. All of this is done, of course, to cause the skeptic to question his beliefs and ultimately upset him.

That’s right, it’s like that one scene from a thousand movies except this time there are silent tools. Read this comic again, then say aloud “this is one of the web’s most popular comics.”

In a recreation of the classic scene from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, a female child ducks into a closet during a game of hide-and-seek, only to discover a portal to a fantasy world called Narnia.

In a not-so-surprising-anymore twist, geek culture is injected into the classic plot-line when the young girl sends an unmanned probe (of her own making) into the portal instead of exploring it herself. In the last panel we see the probe “meeting” the faun Mr. Tumnus, a humorous contrast and combination of childhood memories with modern technology that is sure to delight the average reader.

A man at his desk, surrounded by empty cans of Mountain Dew™, reflects on the magnitude of a particular block of code he has just written. The code he has written is concise, beautiful and solves a seemingly impossible task - it is the perfect code.

After these first two panels, the comic strip becomes a flow-chart. We are presented with two options for who gave this particular problem to the man, along with their respective responses.

Academia: the intelligent female professor excitedly proclaims that this particular piece of code will yield them publishable academic papers, multiple theses and acclaim amongst their peers. This is a common response to anything done by students within a professor’s group. Whatever it is, no matter how trivial or specific, try and make a paper out of it and get funding. This is an effect of the constant cycle of publication and funding that forms a majority of the post-graduate academic ecosystem. I would draw a diagram of this cycle, but that is not my medium.

Business: in this case, an ignorant male boss responds to the man’s code without care or congratulations. He merely comments that the man has fixed a technical problem but more exist, such as the classic IT bug: outlook syncing. These two problems, while wildly different to the engineer, are seen as equivalents to the businessman.

The statement being made is this: in academia, solved problems and new algorithms themselves are important, whereas in business they are seen as things to be used.

Note: this is not new information to anyone.

The Author begins by proposing the classic American comic book scenario, “A ‘radioactive’ ________ has bitten our hero, granting him/her power.” This story line is the history for several comic book heros and villains, including such well known examples as Spiderman. But in a comic and science-related juxtaposition, our author proposes the preposterous and nearly nonsensical “Radioactive Carl Sagan” as the granter of our hero’s powers.

Carl Sagan was a physicist of some television repute. While a scientist of some skill, his most famous and lasting efforts were in his advocacy. He was responsible for creating such h well-known skeptical and science-advocacy efforts as the television series Cosmos and his book, “The Demon Haunted World”. His face and voice are still associated with science, science advocacy, and skepticism throughout the world, despite his death in 1996. Carl Sagan’s goal was to bring the average person to a state of being informed and even excited about scientific progress.

The Author punches this strip by showing then exactly what he believes Carl Sagan’s “Superpower” was: getting people excited about science. Our hero using his “superpowers” attempts to engage someone (who, comically, is not the person who shouts “Help! Thief!” in the first frame) in a dialogue about science. This comic plays on the idea that Carl Sagan’s “uncanny” ability to get even laypeople excited about complex and esoteric topics such as astronomy and physics was itself a sort of “superpower”, which is then compared to the “superpowers” of other heros indirectly.

A female is seen giving technical advice to a male who is attempting to decide which of two smart phones, the Apple iPhone or the Motorola Droid, to purchase. After the female finishes describing the high-level differences between the two devices, the male questions the very nature of his predicament. He wonders if and how he can rid his life of consumerism and the constant desire for the latest gadget, allowing more of his time to be spent on productive endeavors.

The male then pauses, and delivers a humorous cliche in the form of a modification on the now famous Apple advertisement line, “There’s an app or that.”

In a surprise twist, the knowledgeable and confident female character then states that both smart phones do, in fact, “have an app for that.” This is funny because that kind of application could not actually exist.

Then, in an even more comical twist, the female corrects her previous statement by revealing that the iPhone version of the app has been rejected. Based on this new information, the male decides to purchase the more geek-friendly Droid - despite his earlier wishes to live free from electronic devices.

This last scene is humorous because of the widely held belief that Apple frequently rejects applications during their approval process, a belief popularized by bloggers whose applications were rejected by Apple.

Note: this strip clearly plays on the average reader’s automatic preference for the Droid as its software is open-source and created by Google.

This comic strip starts out with a female at a podium making what appear to be campaign promises. She is interrupted from the audience by what is assumed to be a male stand in for the author. He rails against what he feels is an unfair electoral system, totally dismissing her campaign promises outright. Then, in a humorous twist, it is revealed that she is actually just running for class president. The male interloper stammers, trying to formulate a reposté. The punchline is delivered in the last frame when the female inquires as to whether the male learned about politics by arguing on the internet. The male then states that he never thought he would need more than one response, due to the anonymity he had enjoyed online (where he is used to carrying out his arguments).

In summary: socially well adapted female is challenged by a geeky male. She then belittles him publicly. See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Female_domination

It can be assumed that the Author, while watching a television show by himself, heard the line “the moment my brother died, I felt a searing pain in my heart” and immediately sprung from his bean bag chair to write down the line and a single word: “PHYSICS!” That word was then underlined and circled, thus beginning the creation of another scientific-concept-transposed-into-real-life cartoon.

In the cartoon we see a man describing the grief he felt during his brother’s death to a second man. The second man, a physicist, is then shown giving three possible verbal responses that serves as examples for right, wrong and very wrong answers.

The first response is a simple condolence that one would expect for the given situation. The hilarity begins in the second response, in which the physicist takes the word “moment” into the context of his profession, specifically within the topic of causality (cause and effect). He asks if the pain felt (effect) truly happened in the same moment as the brother’s death (cause), or if there was a delay from the speed of light - the maximum speed at which information can travel according to physics.

The third and most ludicrous response from the physicist has him imagining an experiment involving the killing of the first man’s other siblings in order order to use the instantaneous cause and effect to violate the rules of causality and send signals back in time.

There you have it readers, the Author has managed to turn a man’s death into a homographic pun involving physics and time travel.

The adult asks the child a loaded question about her toys. She responds, as any child would, with a simple answer. The adult then corrects the child and proceeds to wax philosophical about how her toys, and thusly the other objects in our lives, are ultimately just the sum of their parts. He then adds that these parts can be reused upon the disassembling of the object.

The last three panels show the child, presumably at the DMV, looking at her toys and deciding to opt in to the organ donor program. This is humorous because the adult’s lecture has led her to think of her organs as Lego bricks - to be disassembled and reused upon her untimely death.