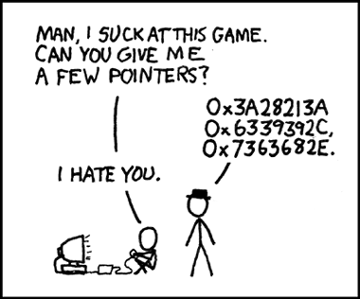

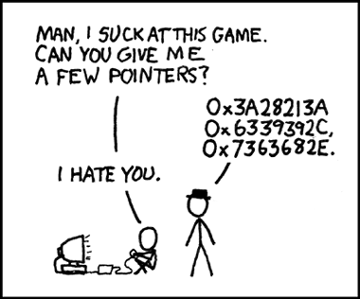

A man is playing a video game and asks his friend wearing the Hasidic Jew Hat to give him some assistance, since he is experiencing some difficulty progressing past a certain challenge. But because his friend is “evil” (as denoted by the Black Hasidic Jew Hat), he responds with unhelpful wordplay of the similarity of the word “pointers,” thus earning the ire of the man who is playing video games.

The Man Wearing the Black Hasidic Jew Hat (further referred to as “Black-Hat” for brevity) is playing off the similarity between the word “pointers” as used colloquially to mean “helpful information or guidance” and “pointers”, which refer to a specific construct in low-level computer programming. When programming in C, C++, or Assembly the notion of a “pointer” or the logical address of a value in computer memory is a lesson that is considered both difficult and essential to master as early as possible in one’s programming career. Black-Hat provides several hexadecimal numbers that are a shorthand for numbers that fit into 32-bit memory. The length of these numbers is significant because they closely match the length used by most computer programmers as they learn to program, and thus should be immediately recognizable to anyone who has been introduced to the field.

Thus, “Black-Hat” answers the player’s query with an honest answer that is simultaneously precise and entirely unhelpful. These homographic puns are considered high art in recognition-heavy geek humor.

CURATOR’S NOTE: While the association between Jewish Fashion and Math might seem to suggest a veiled reference to the racial stereotype: “Jews are good at finance and math,” it does not seem to have been the the author’s intent to draw this allusion. As such, the charitable reader should dismiss it as a artistic curiosity and nothing more.

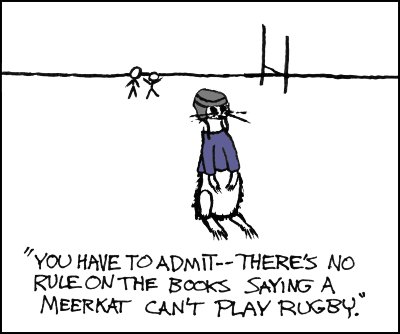

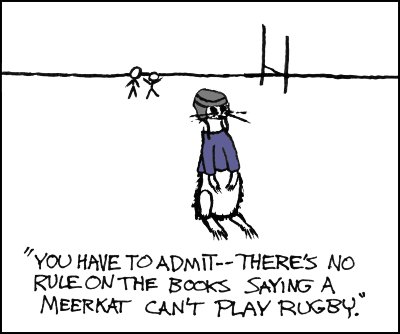

Two men in a field argue about if a meerkat is allowed to play rugby.

Meanwhile, a meerkat in full rugby uniform waits patiently for a ruling.

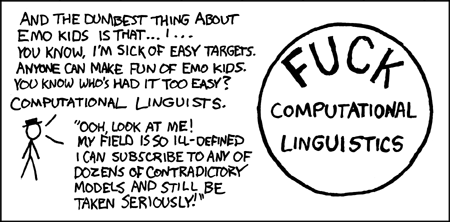

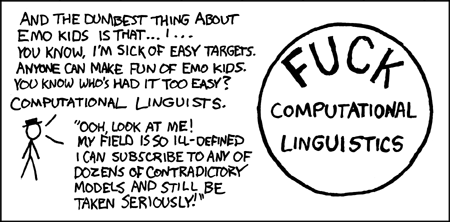

The author begins his thoughtful analysis of the field of computational linguistics with a diatribe aimed at “emo kids”. The term “emo” is short for “emotional” but stands for a genre of music associated with moody teenagers wearing skinny-legged jeans and hoodies from American Apparel. Acknowledging that emo kids are easily ridiculed from the lofty heights of young adulthood, the author focuses his attention instead on a group that has escaped censure, despite riching deserving it - namely, computational linguists.

Computational linguistics is artfully contrasted with a real scientific field where practitioners do not endorse competing models, such as physics. Physicists do not subscribe to competing models and are in uniform agreement concerning a theory that unifies their models of the fundamental forces of nature: gravity, the strong nuclear force, the weak nuclear force, and the electromagnetic force. The theoretical unity of a mature science is celebrated in books such as The End of Physics.

The author conveniently summarizes his insightful analysis of the field of computational linguistics by writing a short bumper sticker slogan and circling it.

The author of the comic understands the comic value of ridiculing minorities and adds the ingenious twist of ridiculing an obscure one.

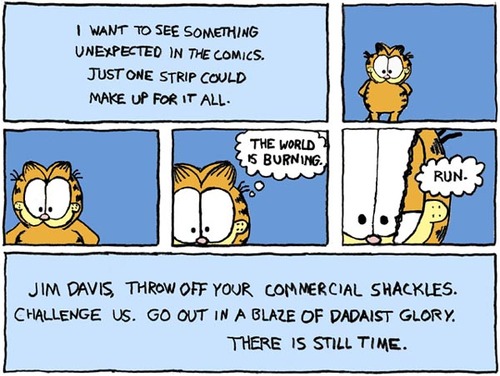

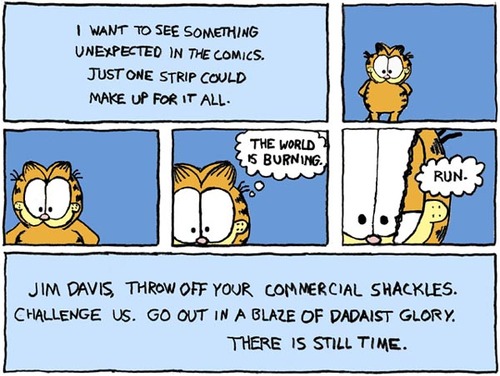

The author challenges Jim Davis to throw aside his formulaic and predictable cartoon style by taking a classic Garfield strip and filling in nihilist dialog. Perhaps he could embrace edgy subject such as math, charts, and geek relationships?

February 6, 2006 at 12:00am

2 notes

Herein the author lies.

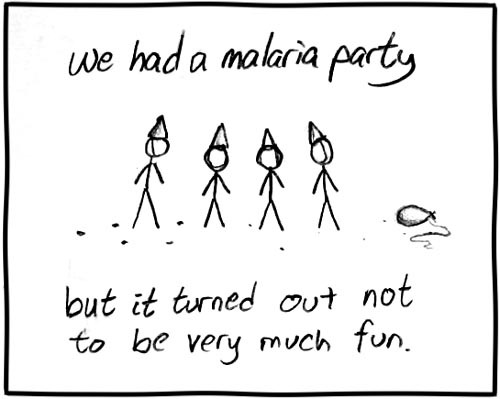

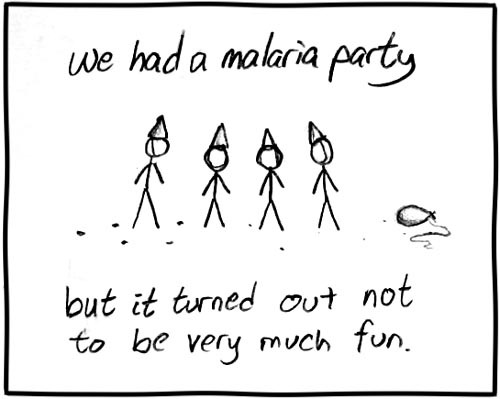

It is a somewhat common practice for parents to have “pox parties” wherein a child with chicken pox interacts with other children in order to expose them to the disease so they can contract it in a controlled manner. The thinking behind this practice is that the parents would rather have the children contract the disease “naturally” (as opposed to vaccination or chance encounters with infected persons) at a young age where they will be more resilient to its effects and can be under the watchful eye of prepared parents. It is assumed that the Author’s family forced his participation in a pox party in his youth.

This strip plays off of the phenomenon of people having “parties” for other diseases modeled after those for chicken pox. People have been known to attempt controlled contraction of measles, hepatitis A, mumps, and the flu at these gatherings. In this instance, the idea of a malaria party is yet another example of the Author’s propensity for arriving at a punchline via comic absurdity, homographic pun, and cultural insensitivity.

One aspect of the strips humor is derived from the portrayal of the scene. The characters are all standing around wearing conical party hats, there is a deflated balloon on the ground, and there is (presumably) confetti on the ground. This is a play on the fact that they are called “parties” even though they are not actually gatherings of celebration. However, it is possible that some of these gatherings do put on a traditional celebratory atmosphere in order to disguise the true intent of them from the attending children.

Moreover, malaria’s vector is generally via mosquitos, not proximity to infected persons. So, unless the black dots on the ground in the strip are actually meant to portray dead mosquitos, there is no way for the gathering to work in the same manner as a pox party. Since malaria is generally considered to be a disease of poverty, mostly killing young children in Sub-Saharan Africa, the thought of having a party to purposefully spread this fatal disease among children instead of vaccination is an absurd and macabre premise for a comic strip, hence the punchline of “but it turned out not to be very much fun.”

January 1, 2006 at 12:00am

1 note

A man is alone in a room, talking to himself. He is saying it is “pretty gay” that he cannot find his shoes.

This strip employs cliché.

22.